LeetCode::Backtracking::Permutation

Introduction

Backtracking is a general approach to solving constraint-satisfaction problems without trying all possibilities.

It incrementally builds candidates solutions, and abadons a solution(“backtracks”) as soon as it determines the candidate cannot be valid.

It can be applied only for problems which admit the concept of a “partial candidate solution” and a relatively quick test of whether it can possibly be completed to a valid solution.

It is often realized by recursion(but not necessarily).

Description & pseudocode

Think of the search space as a decision tree, where each node represents a partial candidate solution, and every possible decision from that node leads to a child node. Backtracking traverses the decision tree in a DFS manner, at each node checking to see if it could possibly lead to a valid solution. If not, it discard all children of that node(pruning), and backtracks to the previous node.

There are several incarnations of backtracking algorithms:

- to determine if a problem has a solution

- to find one solution of a problem

- to find all solutions of a problem

- to find the best solution of a problem

1) determine if a solution exists

def Solve(node):

if node_is_leaf(node):

return node_is_solution(node)

decisions = get_decions(node) # get available decisons for this node

for decision in decisions:

make_decision(node, decision) # make a decision, update node

if not node_break_constraint(node): # pruning

if Solve(node):

return True

unmake_decision(node, decision) # restore state to beginning of loop

return FalseNote: You can also pass the decisions as a function parameter and update them after making a choice for each child node instead of computing from scratch.

2) find one solution or return False if none exists

def Solve(node):

if node_is_leaf(node):

decisions = get_decions(node)

if no decisions:

if is_solution(node):

return node

else:

return False

for decision in decisions:

make_decision(node, decision)

if not node_break_constraint(node):

if Solve(node):

return Solve(node):

unmake_decision(node, decision)

return False3) find all solutions

def Solve(node):

res = [] # to save all the solutions

solveHelper(node, res) # kickstart function for more parameters

return res

def solveHealper(node, res):

if node_is_leaf():

if node_is_solution(node):

res.append(node) # populate res with valid solutions

decisions = get_decions(node)

for decision in decisions:

make_decision(node, decision)

if not node_break_constraint(node):

Solve(node):

unmake_decision(node, decision) Note: It’s a common trick to use a kickstart function for an extra parameter. Here because we want to save all the solutions, we need our recursive function to somehow remember the state when a solution condition is met. To do so, we give it a res parameter and only populate it when the desired condition is met.

46. Permutation

Given a collection of distinct integers, return all possible permutations.

Example:

Input: [1, 2, 3]

Output:

[

[1, 2, 3],

[1, 3, 2],

[2, 1, 3],

[2, 3, 1],

[3, 1, 2],

[3, 2, 1]

]

Solution 1

It is clear that we should somehow use recursion. The typical pattern is to either divide and conquer or decrease and conquer. Namely:

1. Divide or decrease the original problem into subproblem(s)

2. Solve the subproblem(s) using recursion # trivial

3. Somehow put the answers to subproblem(s) together to solve the original problem

It is not difficult to see that for every permutation of length n, if we look past the first element, the remaining part is also a permutation of length (n-1). Knowing we can get ALL the (n-1)-permutation for free by the power of recursion, we look for ways to rebuild the n-permutations with them.

The key insight is that we can insert the first element at all positions of the (n-1)-permutation to get an n-permutation. For example, suppose we want to get the permutations of [1, 2, 3]. Here the first element is 1, and the n-1 permutations are [2, 3] and [3, 2]. We place 1 on all positions of [2, 3], resulting in [1, 2, 3], [2, 1, 3] and [2, 3, 1]. We then repeat the same steps on [3, 2] to get the rest of the n-permutations. A quick check ensures no repeated answers would be generated from this approach.

Code:

def permute(nums):

sols = []

if len(nums) <= 1: # base case

return [nums]

else:

first = nums[0]

tail_perms = permute(nums[1:]) # all permutations of nums[1:]

for perm in tail_perms:

for i in range(len(perm) + 1): # insert nums[0] at all indices

sol = perm[:i] + [first] + perm[i:]

sols.append(sol)

return solsNote: Importantly We don’t need the unmake_decision() step here because slicing creates a new list in Python so the original one is never changed.

Runtime:

\[\begin{align} T(n) &= T(n-1) + (n-1)!\cdot n \cdot \theta(n) \\ &= T(n-1) + cn \cdot n! \\ &= T(n-2) + cn \cdot n! + c(n-1) \cdot (n-1)! \\ &= c \cdot [n \cdot n! + (n-1) \cdot (n-1)! + \cdots + 1] \\ \end{align}\]There is a beautiful trick to solve for this recurrence. Notice that

\[\begin{align} n \cdot n! &= (n+1-1) \cdot n! \\ &= (n+1) \cdot n! - n! \\ &= (n+1)! - n! \end{align}\]Apply this repetitively on each term, we get:

\[\begin{align} T(n) &= c \cdot [(n+1)! - n! + n! - (n-1)! + \cdots - 1] \\ &= c \cdot [(n+1)! - 1] \\ &= \theta((n+1)!) \end{align}\]Space:

Solution 2

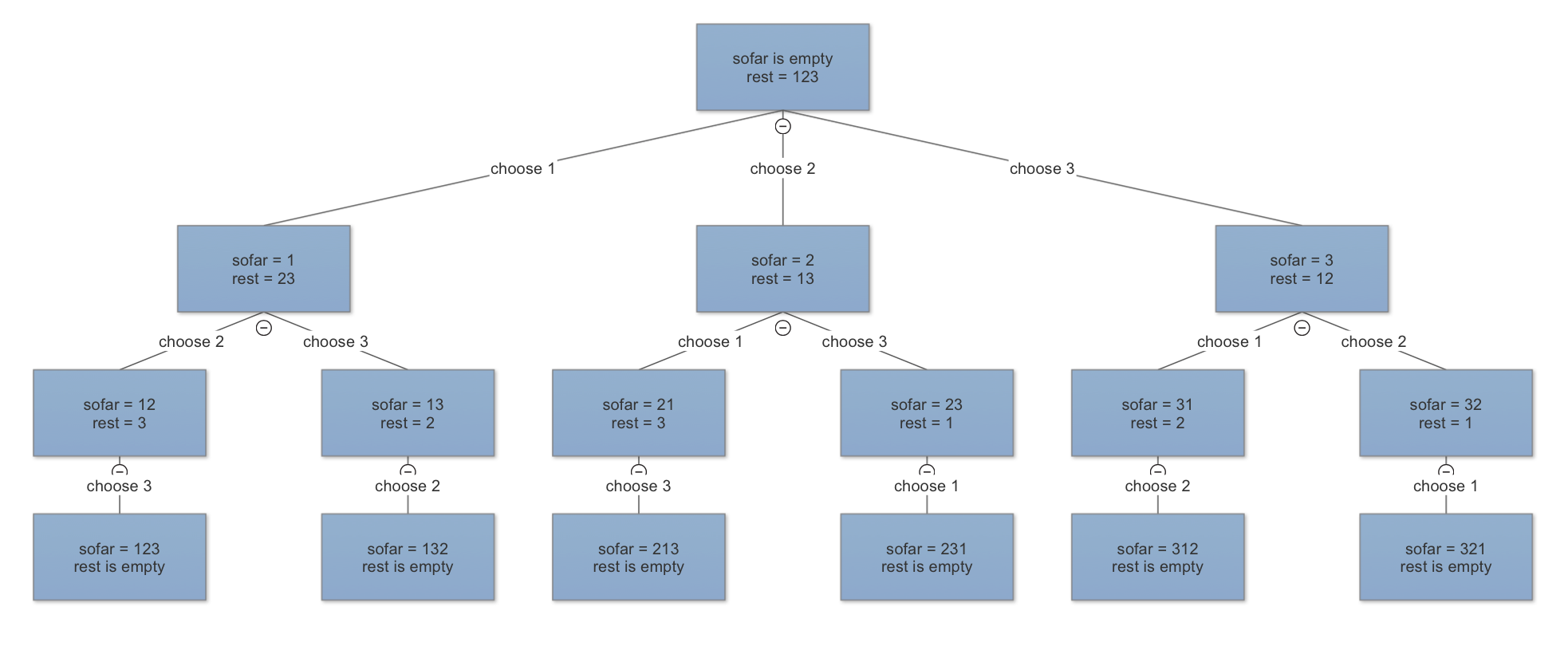

It’s interesting that I started working on this problem knowing it’s under the “backtracking” category, yet the solution I came with up has nothing to do with it. Just plain old recursion. I couldn’t really model the problem in the form of a decision tree untill reading work done by others. The key recursive insight is this: in case of the array “12345”, the permutations consists of the following:

- The number ‘1’ followed by all permutations of “2345”

- The number ‘2’ followed by all permutations of “1345”

- The number ‘3’ followed by all permutations of “1245”

- The number ‘4’ followed by all permutations of “1235”

- The number ‘5’ followed by all permutations of “1234”

As the recursion proceeds, the number of prefix characters increases, and the length of following permutations decrease. Logically we can treat the prefix as decisions we’ve alread made so far (initially empty), and the rest as candidate decisions (initially the entire string/numbers to be permutated). Notice however that this problem takes slightly different arguments compared to the original problem. As always, we use a wrapper function to make it consistent, which is convinient since we will need one for saving all the solutions anyways.

def permute(nums):

ans = []

permuteHelper([], nums, ans)

return ans

def permuteHelper(sofar, rest, ans):

if rest == []:

ans.append(sofar)

for i in range(len(rest)):

permuteHelper(sofar+[rest[i]], rest[:i]+rest[i+1:], ans)

Runtime:

\[\begin{align} T(n) &= n \cdot [T(n-1) + \theta(n)] \\ &= nT(n-1) + cn^2 \end{align}\]Space:

Solution 3

It turns out there are many more interesting ways to generate permutations, many of them beyond the scope of this post. I will however cover another one because I find the idea extremely elegant.

def permute(nums):

ans = []

permuteHelper(nums, 0, ans)

return ans

def permuteHelper(nums, k, ans):

if k == len(nums):

ans.append(nums[:]) # important

return

for i in range(k, len(nums)):

nums[k], nums[i] = nums[i] ,nums[k]

permuteHelper(nums, k+1, ans)

nums[k], nums[i] = nums[i], nums[k]It took me a while to realize that this solution does exactly the same thing, but in place. It uses k as a seperator, such that num[:k] corresponds to the sofar set and nums[k:] corresponds to the rest set. In making a choice, say nums[i], we

- make sure $ i \ge k $ courtesy of

for i in range(k, len(nums)) - transfer it from

resttosofarbynums[k], nums[i] = nums[i], nums[k] - increase

kby 1 to indicate that we’ve made a choice - check if

kreaches the end of array, this is the same as checkingrest == [] - unmake any change from step3, since this time we are not creating a new list

Only works on mutable data .

77. Combinations

Given a collection of distinct numbers and a number k, return all possible k-combinations.

Example:

Input: nums = [1, 2, 3, 4], k = 2

Output:

[

[1, 2],

[1, 3],

[1, 4],

[2, 3],

[2, 4],

[3, 4]

]Note: I slightly modified the original leetcode problem to make it a more general. In the original problem we have as arguments n and k and is asked to generate k-combinations from numbers 1 to n. Not only does it unnecessarily implies that the elements are in sorted order, this notation makes it impossible to refer to numbers with starting point other than 1, such as 2, 3, ..., n.

Solution 1

The underlying idea is very similar to that of generating permutations, with one important difference: do not look back. This means when making a decision, we should only choose from a pool of decisions that have not been made before (not couting recursive-subproblems) to avoid repitition.

For example, suppose we want to generate all 3-combinations of [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. We start by choosing 1 as our leading element and append with all the 2-combinations of [2, 3, 4, 5]. Then we move on to choose 2 as our leading element, and follow it by all the 2-combinations of only [3, 4, 5].

def combine(nums, k):

res = [ ]

combineHelper([ ], nums, k, res)

return res

def combineHelper(sofar, rest, k, res):

if len(sofar) == k:

res.append(sofar)

elif len(sofar) + len(rest) < k: # make sure there are enough elements

return

else:

for i in range(len(rest)):

# permuteHelper(sofar+[rest[i]], rest[:i]+rest[i+1:], ans)

# Only look ahead

combineHelper(sofar + [rest[i]], rest[i+1:], k, res)![3-combinations of [1,2,3,4,5]](/assets/combination.png)

Solution 2

def combine(nums, k):

sols = []

if k <= 1: # base case

return [[num] for num in nums]

else:

for i in range(len(nums)):

if len(nums) - i >= k:

combs = combine(nums[i+1:], k-1)

for comb in combs:

sol = [nums[i]] + comb

sols.append(sol)

return solsreference:

https://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs106b/cs106b.1188/lectures/Lecture11/Lecture11.pdf

«Programming Abstractions», Book by Stanford

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/print-all-possible-combinations-of-r-elements-in-a-given-array-of-size-n/